Overcoming Cultural Barriers and Increasing Organizational Strength through Managerial Reforms

– Italy: Parlaying Success in Our Chinese Business to a Global Expansion –

After Casappa entered the market in Shanghai, China, in 2005, unique Chinese cultural barriers awaited it. In order to change a culture that stresses the individual more than the team and Chinese managers who at the time didn’t understand their goals, responsibilities, or the need to manage their subordinates, in 2012 the company began reforms together with JMAC. We report on this trial-and-error process, what changes became evident, and the prospects for the future.

Cultural differences are what you should care about the most when entering the Chinese market

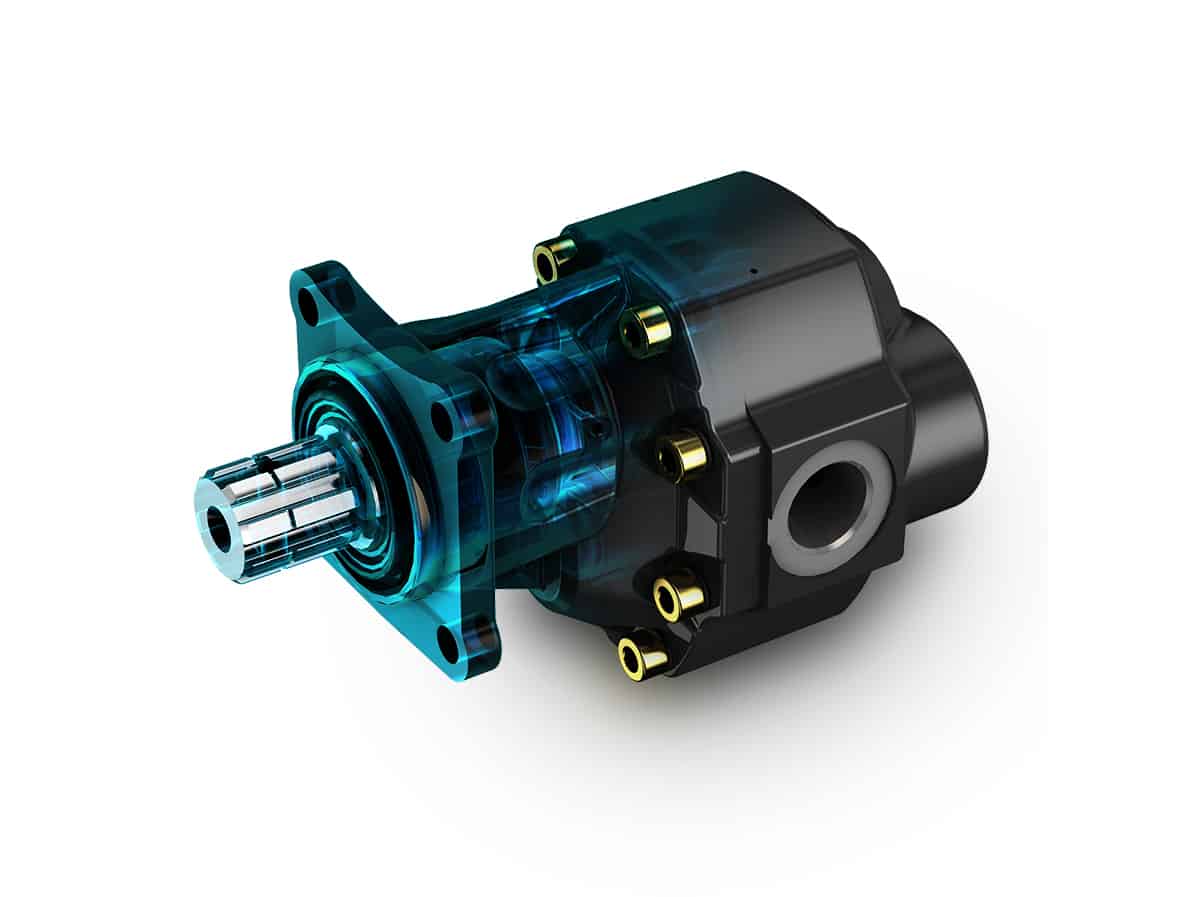

Casappa is a parts manufacturer based in Italy. Founded in 1952 by Roberto Casappa, it began its business by making hydraulic pumps. The company, which currently manufactures gears, piston pumps, motors, and filters for trucks and construction machinery, now operates not only in Italy but also in the US, Germany, France, Korea, China, Brazil, and India, supplying parts worldwide. It is a leading company in its industry, partnering with a whole list of big-name global corporations such as Caterpillar, Daimler, and Komatsu and Yanmar of Japan. Its management policy is to create a business network that covers the entire world and to make customer satisfaction its primary mission.

It entered the Chinese market in July 2005 for the purpose of identifying and incorporating local needs and feedback, and established the Casappa Shanghai Office in a joint venture with one of its group companies, Walvoil. The company then established CASAPPA HYDRAULICS (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. in 2008 as a manufacturing base from which it planned to expand its Asian market. It now has approximately 150 employees. It was harder than the company had initially imagined to operate its business in China, whose culture, values, work methods, management style, etc. differs from Italy, and to establish its business with stable product quality.

Andrea Amaini, who assumed the post of general manager from after the Chinese corporation was established until October 2013, looks back on that time. “Before I took over, my predecessor didn’t explain anything about how I should keep up with manufacturing information or manage the accounting, and only told me I just needed to worry about cultural differences. Also Mr. Renato Casappa, our president before I left for China, handed me a book about Mannerisms in China. I read it, and my impression of it at the time was that it was a fitting book for people in service and marketing, but didn’t apply to me, since I would only need to do what I had done in Italy in terms of running our manufacturing business and carrying out our manufacturing plan.

“But that idea was completely turned on its head after I took over. Today, if someone asked me what’s difficult about running a company and doing business in China, I would immediately say, ‘Cultural differences,'” Amaini laughs, indicating how difficult cultural differences can be in China.

A cultural difference that values the “individual” over the “team”

What was different in particular? That the Chinese tend to prioritize the individual over the group or team. “In Europe and every other country I’ve had experience with, the team would always deal with a problem and discuss it together,” recalls Amaini. “But in China, that’s very difficult. The Chinese members weren’t used to working as a team.”

A common story we hear in China is that Chinese employees will ask, “Why is it important to work with other people in a team?” or “Why is teamwork important?” As in the Chinese proverb, “A single Chinese person is a dragon; a group of Chinese people is an insect,” we must run our business with the understanding that the Chinese don’t really get the concept of working on something as a team.

Shortly after assuming his post, Amaini noticed several Chinese managers quit the company. One of them quit when Amaini relocated an employee that wasn’t suited to his position.

In order to restructure the Chinese managerial positions, Amaini needed to recruit people and develop an organization where practical managers could work as a team. Facing the situation in China, Amaini sought a partner with whom he could tackle this issue. One potential company that the Italian headquarters brought up was JMAC. The criteria they looked at were the company’s record of supporting manufacturing businesses, its ability to provide the same service in any region around the world, and its competitiveness in China. The deciding factor was JMAC’s knowledge of how to improve the productivity of a manufacturing plant, which was the next item on their list, and in particular, its expertise on Lean Production and its ability to offer solutions that connected these two issues.

The reforms are launched! The key is to innovate Chinese managers

In April 2012, Amaini started his reforms with JMAC. He first conducted workshop-style training sessions on Lean Production, followed by practical training on lean management, both supported by JMAC. He also began reforms on human resource management at the same time. This human resource management reform used JMAC’s human resource management (HRM) diagnosis program to clarify company’s current state of HRM through questionnaires and interviews with Chinese managers. The results showed that while topics such as the company’s human resource training system and compliance were highly rated, issues came to light concerning trust between Chinese employees and Italian top management. Specific important issues included management’s not delegating enough authority to Chinese managers and the unclear career prospects of Chinese managers. The Chinese managers’ disappointment in the fact that management didn’t delegate enough to them, and their concerns regarding their unclear future, had led them to distrust management.

In response to this evaluation, the company launched an Empowerment Project for all Chinese managers. This project aimed to making managerial-level Chinese employees think and work together as a team while improving the individual capability of Chinese managers.

Each Chinese manager conducted JMAC’s self-evaluation, while Amaini, with JMAC’s support, interviewed each and every manager to identify which skills the manager had and which needed improvement. Individual action plans were also drafted, aimed at developing capability. At the same time, managers were given goals and responsibility in their roles. “We gave all Chinese managers–including new ones–a goal, and by teaching them how to review their subordinates’ work, we helped them to understand their responsibilities. And we shared the awareness that it is by achieving these goals and responsibilities that they would prove that they have done the job of a manager. We also set a common goal for all Chinese managers,” Amaini says, explaining one of his solutions.

But things wouldn’t be so easy in this formidable Chinese culture. “What we found difficult was getting them to realize that they too were part of the problem. They were extremely critical of the company at first, and in order for them to talk more frankly, we started by listening to the many things they were dissatisfied with about the company.”

One division made an effort to draft rules and guidelines for managing the production of products of a certain level of quality, managing costs, and taking control. “We want you to do this.” “We don’t know why it has to be that way…” “Don’t worry, just do as you’re told.” Everything initially seemed to go well after these conversations. But problems arose later on.

Amaini explains, “The Chinese managers weren’t convinced. Not only didn’t they understand why they had to do the work, they didn’t know why they even had to manage people. Once they did their job, that was it; when they were done, they waited for the next command and simply did what they were told to. This was one of the biggest differences between the Chinese and Western managers. Managing the results of their work is common practice for Western managers. It is a PDCA (Plan/Do/Check/Action) cycle of sorts. When you do your job, you have to check whether the results were good or not. But in China, there was no concept of managing.” Here again, Amaini suffered the effects of cultural differences. These were cases where he learned that simply applying his native country’s methods to China doesn’t work.

JMAC CHINA consultant says that “Empowerment” is a sensitive topic capable of significantly affecting not only human resource management, but also corporate management as a whole. “As a consultant, I tried to handle matters calmly so that the project always remained on track, and particularly to avoid emotional conflicts. Sustaining the project members’ passion was also an indispensable driving force of the project,” he says.

Changes begin to appear among the managers

Amid all this, changes began to appear little by little. “The initial stages of the project were really tough, but as the project progressed, managers began giving their opinions without hesitation,” says Davide Bruschi, who became general manager in November 2013. Bruschi is Amaini’s confidant, having shared good times and bad times with him for three years as his Operation Supervisor. “This was our biggest success. In time, the project began moving forward, with the Chinese managers, Italian top management, and JMAC working as one.”

As for how he established common goals for the managers in all divisions, Amaini explains, “I believed that if a manager had the same goal as somebody else, they would have something to share, and that would lead to cross-functional actions.

“Some of the goals or KPIs need to be done as a team. As one such action, we launched a Quality Guarantee Project. This required all the divisions involved to draft a Quality Manual, which can’t be done unless divisions cooperate with each other. By having all the managers work on quality, which is the heart of business operations, it gave them the opportunity to develop an awareness of what a team is,” Amaini says.

They would later take steps to increase net profit. To increase net profit, each division needs to make the optimal decisions. The sales division must increase sales, and manufacturing must cut costs. HR must hire good people at the optimal wages. “This project made all the managers understand their goals and results, and helped them understand the meaning of managing and surely delivering results,” says Amaini.

Leadership demonstrated! Managers evolving

Another project involving the supply chain is also under way, and it seems that changes are evident here as well. “It’s still in the first phase, but the leadership of one Chinese manager is enabling human resources and information to flow smoothly, not only among members of his own division, but across divisions as well, and moving the project forward. I think we are seeing the rise of Chinese managers who can demonstrate leadership while maintaining a mindset of working together,” says Bruschi.

Amaini says that through this latest series of actions, “JMAC not only provided programs and the opportunity to improve efficiency as well as see results, but also trained Chinese managers to become in-house consultants. I feel that strong Chinese managers are being developed so the company will be able to run on its own even after the project ends.” Bruschi also evaluated JMAC, saying, “JMAC has a vision not only of how to be efficient, but also what lies ahead, and what differentiates it the most from other companies is that it offered us management support as well.”

JMAC consultant explains that it was an important process. “Throughout the project, the Italian management team and the Chinese managers talked face to face. By talking what they think, there were occasional conflicts that came from the differences in culture and values, but I believe that those things were what improved the relationship of trust between the two sides.” He also mentioned that the reform of the corporate culture began making progress when management realized that human resources weren’t just resources but instead the most valuable asset of the company, and when they conveyed that idea throughout the company.

Learning and improving from experience in China: Aiming for further globalization

While running a business in China is harder than he expected, Amaini says that the first step to success is to take full advantage of the power China has. “China is moving forward at an incredible pace. We mustn’t stop that momentum. It’s within that speed that we should set guidelines as best we can and maintain control. A management method that takes advantage of China’s power is what I think we need.” To do this, communication is an indispensable foundation. “Interpersonal relationships are difficult, even among people in the same country who speak the same language. A manager’s skill is best tested when he is leading a team and managing people. By hiring people of similar ages, work experiences, and backgrounds, we were able to create a team more easily. And management’s role is to disseminate Casappa’s values to all employees,” says Amaini.

Bruschi, who took over the reform, says, “The three years we spent together developing a great team was a time in my life that required professionalism the most. Casappa needed a streamlined process, but more than that, it needed a corporate philosophy that would change how the managers in all divisions and all employees thought.”

Casappa continues to innovate to become a more global corporation. “There are so many things that we gained through the difficulties we had in China. Particularly important was a way of understanding people from a different culture. That has now become part of my DNA, my value and skill. I believe I have improved my ability to lead a team, to work, and to understand other people. I hope to take this experience of success in China to our headquarters and to Casappa offices around the world,” says Amaini, eyeing a global expansion.

Bruschi, who took over his post, says, “Through this latest project with JMAC, local managers have developed a trusted relationship with the headquarters in Italy, and have formed a foundation from which employees can see the future, have hope, and work together. To solidify this, I believe I need to develop a cross-functional team. Don’t settle for current conditions; keep aiming higher–that’s Casappa’s DNA.” Due to the project in China, the Italian headquarters has launched a policy management project with the support of JMAC Europe. We look forward to Casappa’s further developing its cross-functional operations worldwide.